Collections Films

Behind the scenes

Management of new Entries in the Film Collections Department

CINEMATEK regularly enriches its collections thanks to deposits and donations received from Belgian distributors and producers, as well as collections from Belgian and foreign institutions and individuals. Before they can be stored in our air-conditioned warehouses, these items go through various stages:

Pre-inventory

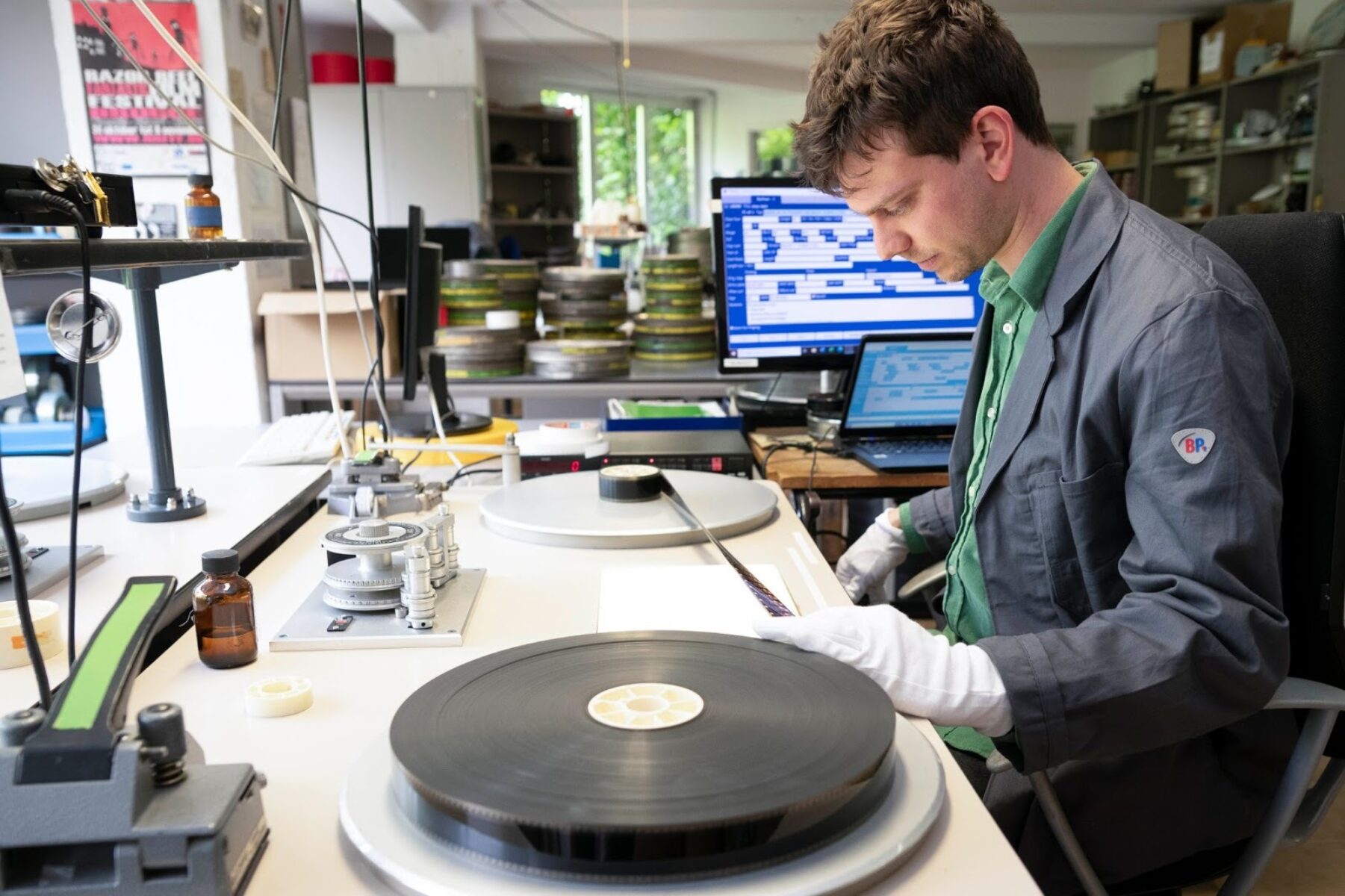

& Analysis of Film Items

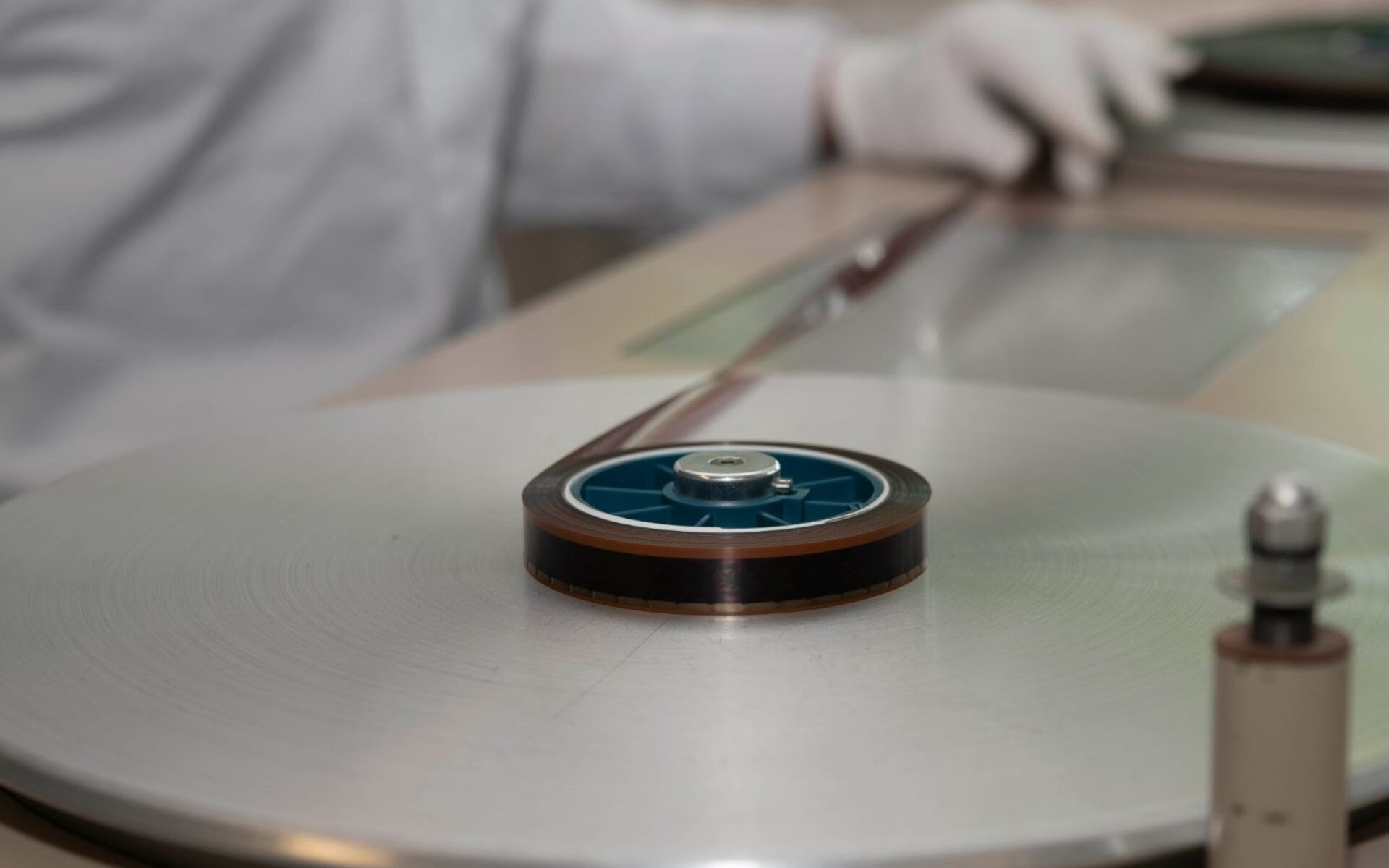

The archivists undertake a physical analysis of the elements to establish their state of preservation.

Particular attention is paid to odours, mould, dirt and rust, as well as visual signs of decomposition. This makes it possible to determine in advance the storage conditions under which the item should be preserved and, above all, to intervene rapidly, if necessary, in order to apply any necessary procedure to ensure the preservation of the item. Films in an advanced state of decomposition, showing mould or affected by vinegar syndrome, are isolated from the rest of the collection and placed in a dedicated area of the archive for the treatment of damaged films.

Reconditioning

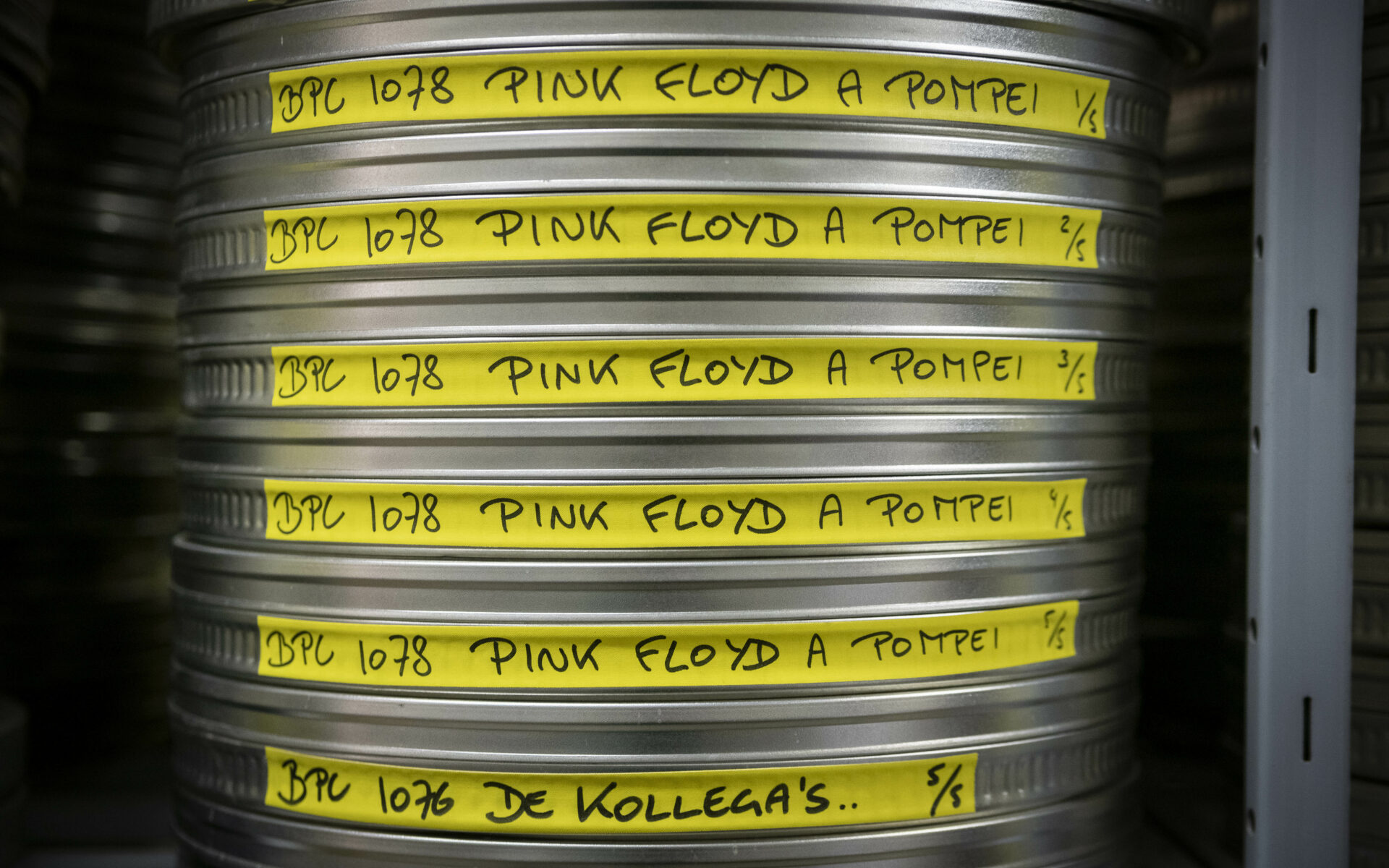

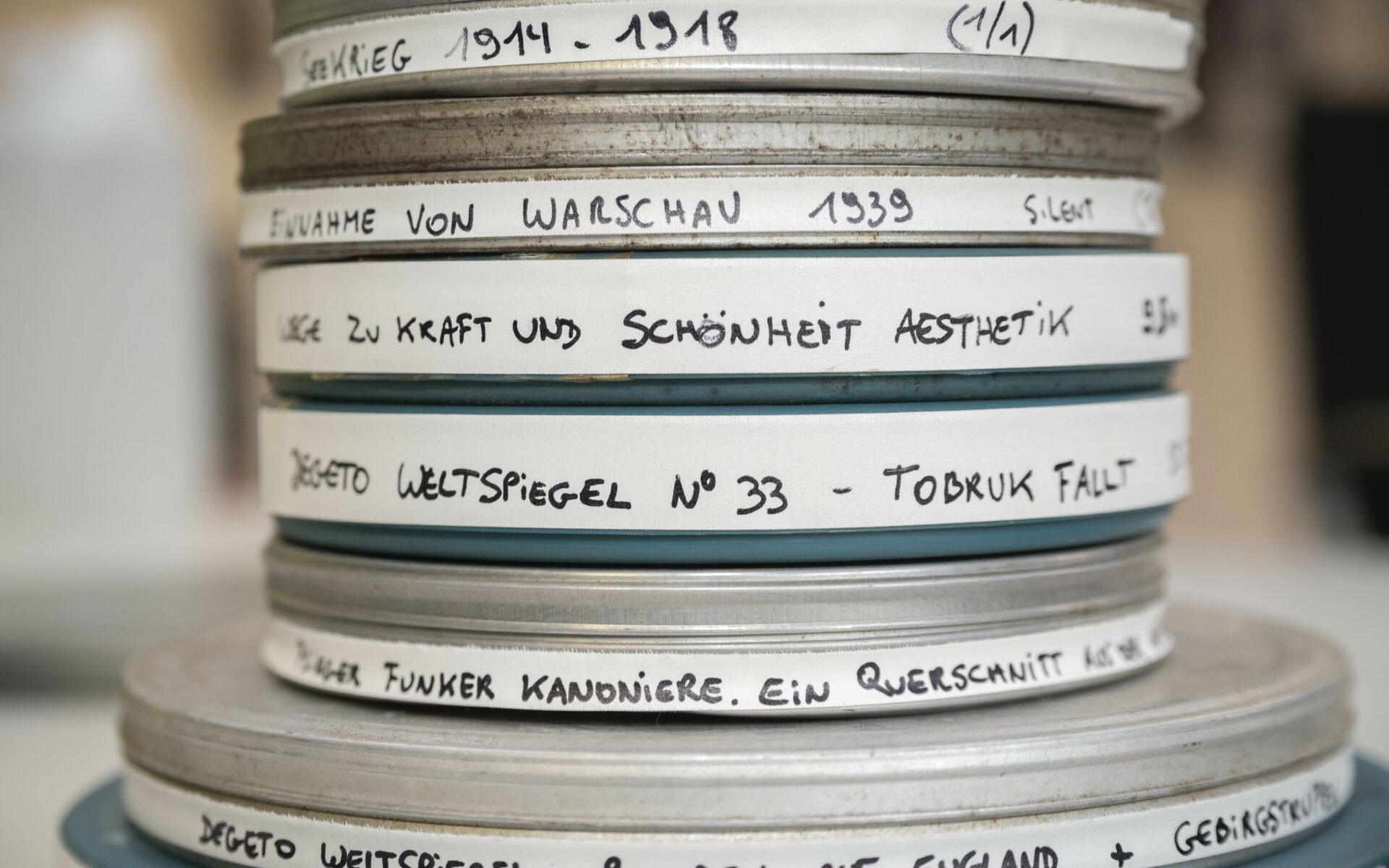

It is important that film items are preserved in clean film cans.

Anything inside the can, such as paper, is also discarded. However, it is repackaged and stored separately, as it is made up of other materials that react chemically with the pellicle and endanger the proper preservation.

If the can shows signs of rust or other damage and is therefore no longer suitable for optimal protection of the element, we will repackage it in new film cans. During this process, it is essential to collect the information on the old can in order to preserve any data relating to the film item.

Identification

of items and cataloguing

Before any item is stored in the archive, it must be encoded in the database. To do this, we collect all the information needed to identify new entries.

In order to identify a film, it is essential for us to know, among other things

The title

The name of the director

Original language

Duration

The year

Country of origin

Production company

Some of this information may be on the film can or on the film itself. If not, the archivists conduct a more thorough search, collecting any information that might be useful for identification.

The archivist then begins to analyse the film text: he or she tries to identify the actors but also any detail that can help to date the film and, subsequently, to identify it - costumes, cars, trains, newspapers of the time, sets, etc. If this information is fragmentary or missing, documentary research is necessary.

For fictional works, we can consult online databases and/or catalogues specially designed for professionals.

For documentary films, experimental films, advertising films and/or newsreels, these searches are much more complex as there are far fewer specialist sources available. In these cases the film item becomes the only source for identifying the film.

Then, in order to ensure the correct cataloguing of new entries in our collections, the archivists inspect the items in order to collect all the technical information essential for the inventory:

Media type

Duration of projection

Number of reels

Format

Frame rate

Image format

Black and white film/colour film (Gevacolor, Eastmancolor, Ferraniacolor, Technicolor...)

Speech/mute and sound type (Mono, Dolby Digital, Dolby Digital Surround....)

Original language

Subtitle typology

Filing and storage in stocks

Once the films have been identified and inventoried in the database, they are then filed according to a defined placement by an assigned classification number. This allows the item to be located within our extensive collection. The items are stored in different locations depending on the type of pellicle: nitrate, acetate and/or polyester.

Preservation

CINEMATEK’s collections are stored according to the preservation standards defined by the archival community, in air-conditioned premises. Films on pellicle need to be preserved under specific conditions of controlled temperature and humidity. This is due to the organic nature of the components of the various pellicles - cellulose nitrate, cellulose diacetate, cellulose triacetate - which degrade in the presence of high or low temperatures and humidity. One of the fundamental principles of preservation is therefore to control the environment in which films are stored to prevent their degradation.

Until the 1950s, film was produced on cellulose nitrate pellicle. These films require very strict preservation conditions as they are highly flammable. It is recommended that they are preserved at a maximum of 2°C and 20-30% RH (relative humidity) in rooms outside living areas. For its valuable nitrate collections, CINEMATEK has a special nitrate preservation facility outside Brussels. Archivists monitor the collection on a weekly basis to ensure its long-term preservation.

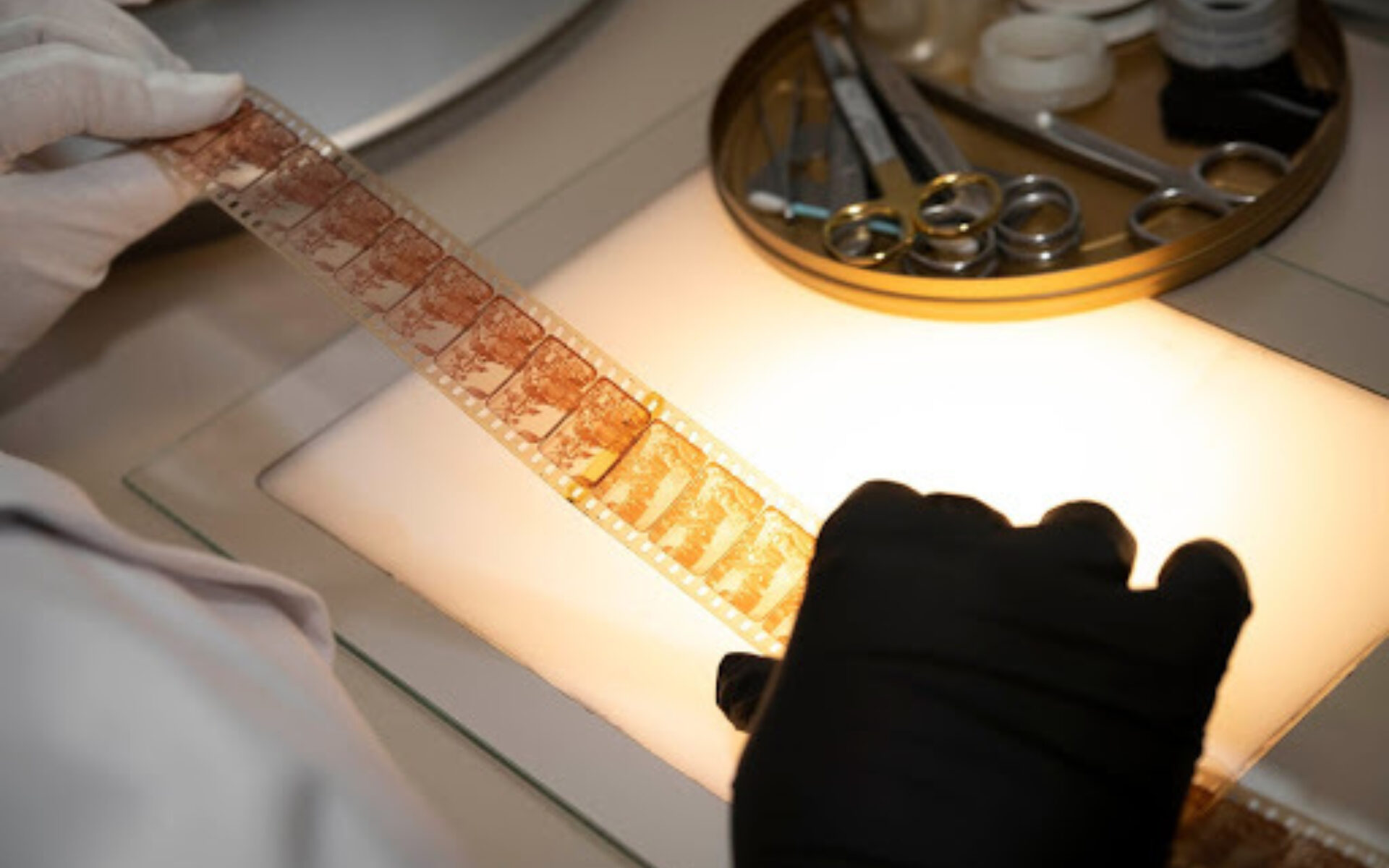

Another preservation problem is the cellulose acetate pellicle, which was used for copies until the early 1990s and is still used today for film negatives shot on film. Over time, chemical decomposition can alter the level of acetic acid naturally present in the pellicle - a phenomenon known as "vinegar syndrome". To prevent this deterioration, it is recommended that black and white acetate film be preserved at 7°C and 30% RH, and colour acetate film at 2°C and 30% RH. As the pigments in colour films are very sensitive to this degradation, a chromatic dominance of the image - often red or magenta - may eventually result from this alteration if the films have not been stored under optimal conditions before joining our collections.

Since the early 1990s, the films have been printed on polyester-based pellicle, a plastic material that has proven to be very resistant, stable and, for black and white copies, can be preserved at room temperature. However, colour copies are subject to the same preservation constraints as acetate copies.

Restoration and digitisation

In addition to its preservation activities, CINEMATEK carries out an important activity of digitisation and restoration of film heritage.

Digitisation

CINEMATEK carries out numerous digitisation projects in order to ensure that the film heritage is made available in digital form. Digitisation allows access to film materials for scientific research and/or the creation of new productions through modern digital distribution channels. Digitisation is mainly used for documentaries, newsreels and small-format films where easy access by researchers and audiovisual professionals is required. It also ensures the preservation of the original media by reducing access to them, thus avoiding any risk of damage during viewing.

Restoration

Each restoration aims to make a film possible to be screened again, while preserving a version as close as possible to the version as it was first seen in the cinema. Some films can no longer be screened due to mechanical damage caused by the heavy wear and tear to which some prints were subjected during their passage through the projector. Other films, in an advanced state of decomposition, require emergency preservation to avoid the disappearance of the film itself.

History of the conservator’s work

Restoration work is always carried out on a copy, a reproduction of the original work, and not on the original version itself. Cinema is industrial, serial and reproducible in nature: the concept of the original in the field of cinema therefore differs from that of other art objects. Moreover, each restoration is the product of the techniques of a given period and is influenced by the aesthetic values of that same period. The ethics of restoration also lie in the importance of documenting the choices made. Every effort is made to produce a version as close as possible to the original, yet each consciously restored copy is a unique object. Restoration records that document each phase of the process allow any restoration to be reversible: this is one of the fundamental ethical principles of restoration.

During the 1960s and 1970s, restoration activities (cleaning the pellicle, repairing tears and perforations, making prints, etc.) consisted of reproducing the narrative content of the film without really considering its aesthetic qualities. From the 1990s onwards, the concept of not limiting oneself solely to safeguarding the content of a film, but also taking into account its aesthetic characteristics, became established, leading to the birth of the profession of restorer. The arrival of digital technology in the early 2000s also changed the world of archives, as it raised essential issues relating to respect for the ethics of restoration, as well as to the budgetary management of restoration activities.

Technical stages of a digital restoration

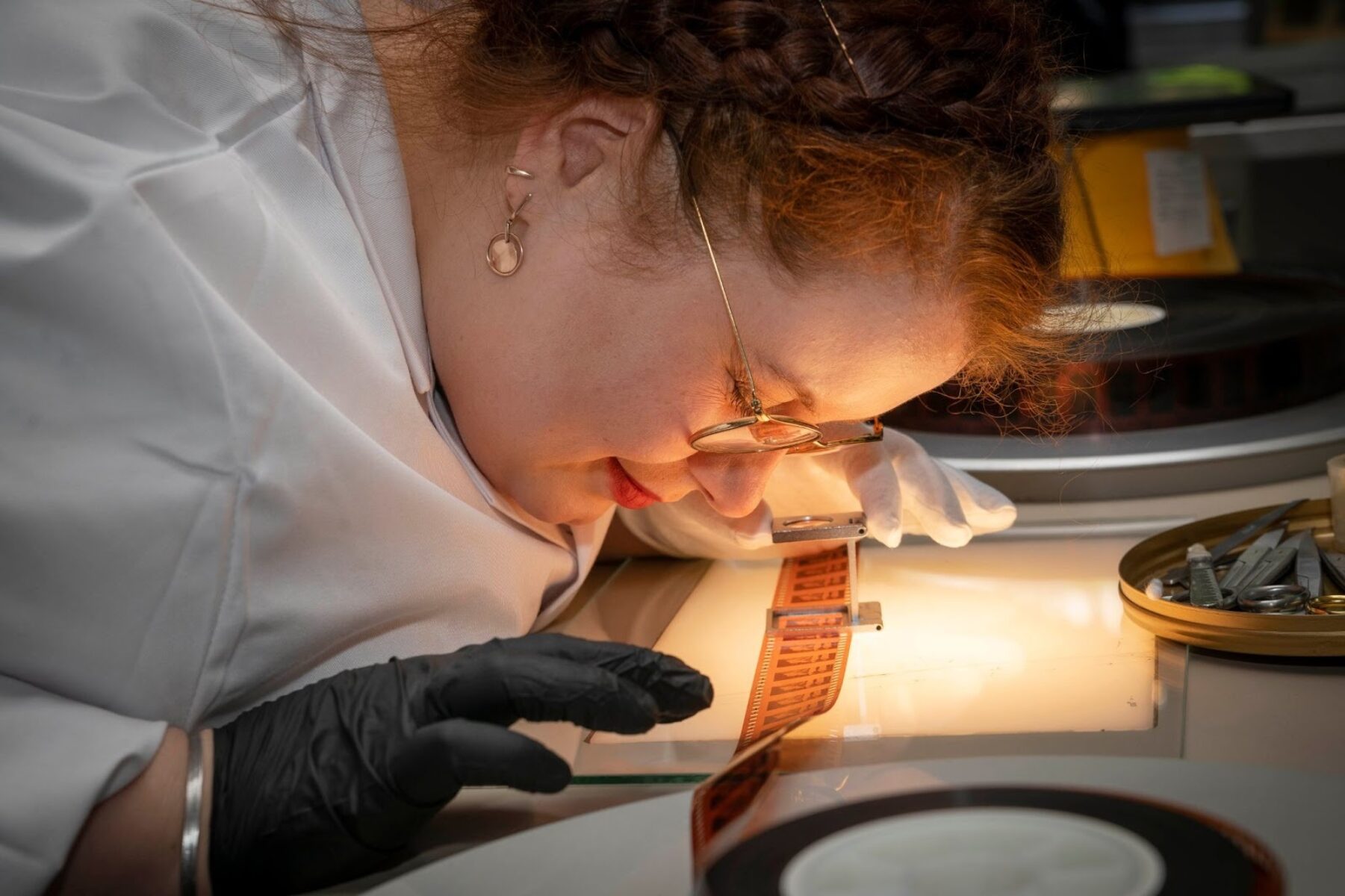

The first step in a restoration project is a thorough study of the work and a selection of the best elements from which the restoration will be carried out.

Once the restoration elements have been selected, we prepare them for scanning. This stage consists of repairing damaged parts, reconstructing missing perforations, redoing collages, etc.

In a third step, we clean the pellicle to remove the dirt left by time.

Once the elements have been repaired and cleaned, we scan the image and sound using equipment specially designed to meet the needs of the archive.

The digitised image is then stabilised and cleaned. Using software, the damaged parts of a photogram are treated and replaced by "clean" parts detected in other photograms from the same sequence. It is important that the interventions remain imperceptible and that no digital artefacts are created. It is therefore sometimes necessary to preserve scratches and stains. Digital tools make it possible to go further in the restoration work, but the conservator/restorer must ensure that the original version is respected in its entirety. In particular, the conservator/restorer ensures that there is no intervention on defects linked to the technical means used at the time when a film was shot (e.g. camera hairs or instability).

The same philosophy is applied in the last phase of restoration: colour correction and/or calibration. These procedures restore the original colours of a film. This is done by using a reference copy when the films are very old. In the case of more recent films, we also work closely with the director or director of photography.

Digital preservation: a new challenge

In recent years, the film industry has been revolutionised by the so-called digital revolution. Films are now shot, edited, projected and saved on digital media. In addition to films on "native digital" media, films on analogue media are increasingly digitised. In order to ensure the long-term preservation of all these digital elements, CINEMATEK has developed a platform and a workflow based on open formats. Furthermore, in order to ensure the storage and protection of digital data, it is imperative to consider the growing importance of the budget allocated to this activity. All digital films deposited at CINEMATEK are carefully checked and catalogued before being stored in our digital archive - servers and LTO tapes. Technical and descriptive metadata about the film is also entered into our database. The data is stored on LTO (Linear Tape-Open) tapes, an open-format data archiving technology that has proven to be a successful innovation in digital storage in various sectors.

Unfortunately, this system also shows some disadvantages: LTOs, like all digital storage media, have a limited lifespan, which requires a continuous - so-called "perpetual" - migration of files to new generations of better performing LTO tapes.

A second problem is the uncertainty that current files may not be compatible with the drives that will be produced in the coming years, which will require file conversion. It is therefore imperative to save the film in the best possible quality, in the highest definition. The amount of data that makes up a film is colossal. The standard format for digital projection is now 4K: this means that a feature film in 4K format can easily be as large as 4 or 6 TB - Terabyte (or equivalent to over 200 Blu-ray discs).

In addition to perpetual migration, backups are the second pillar of a digital backup strategy to ensure long-term digital preservation. Digital films are backed up on at least two identical LTO media, which are located at a separate site in our preservation centre.

Standardisation in born-digital film delivery

Standardisation of formats is essential in the process of developing digital preservation. Ideally, the workflow of post-production companies should be aligned with the procedure adopted by archives. For this reason, for some years now, the following elements concerning new Belgian film productions have been deposited at CINEMATEK:

The uncompressed master, also called Digital Cinema Distribution Master (DCDM).

A Digital Cinema Package (DCP) projection copy, with the different language and subtitle versions. This projection copy must not be encrypted (a technique used by the industry to secure access to the film).

A reference file or mezzanine file. This is a lightweight file used for TV or online broadcasting and for producing masters, e.g. a DVD.

In order to complete the preservation of a cinematographic work, non-compressed files relating to the documentation of the film’s release (film-related collections: photos, posters, digital press kits, scripts, etc.) are also deposited at CINEMATEK.